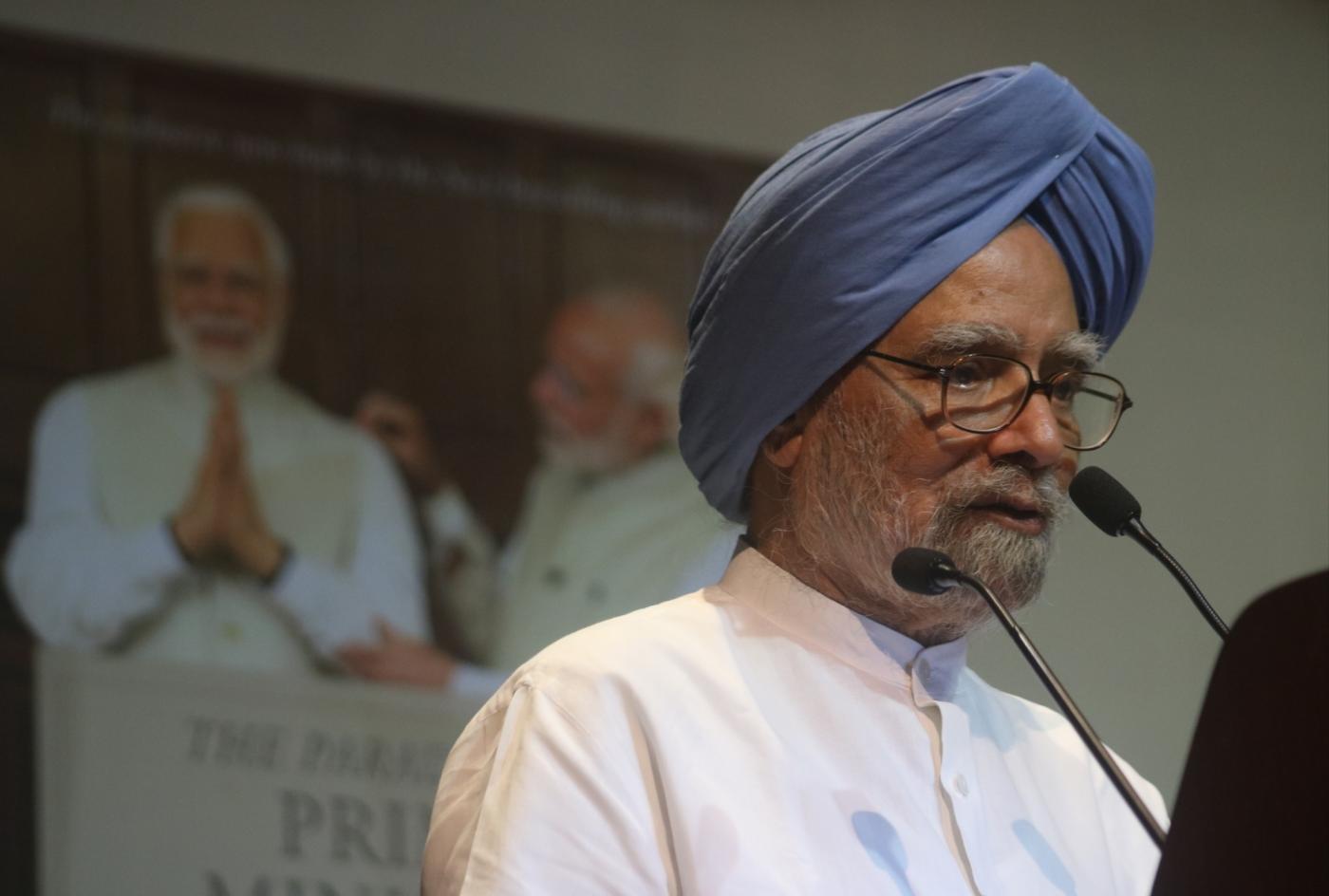

It’s rather ironic that Manmohan Singh, who unleashed sweeping market reforms in 1991, should have presided over their virtual demise during his second term as Prime Minister (2009-14)…writes VISHNU MAKHIJANI

Then, what if Manmohan Singh had not needed his bypass surgery in January 2009 and had carried on holding the additional charge of finance?

“As it turns out, destiny had a hand too in the grave mistake the UPA made by bringing (Pranab) Mukherjee into the finance ministry ahead of Singh’s bypass. With Singh indisposed, perhaps the decision makers had no choice. But it has become increasingly clear that the Congress and the economy have paid a heavy price for it,” award-winning journalist Puja Mehra writes in her new book “The Lost Decade – 2008-18; How India’s Growth Story Devolved into Growth Without a Story” (Penguin).

Before Mukherjee’s appointment as Finance Minister, Mehra writes, India was on the verge of being christened a “miracle economy”. By the time Mukherjee exited (in July 2012 to become the President), large fiscal deficits and a huge international debt position had made the country vulnerable to global financial shocks and terms-of-trade shocks.

“Within a year, India would earn the ignoble distinction of being one of the ‘Fragile Five’ economies,” writes Mehra, who won the Ramnath Goenka Excellence in Journalism Award in 2008 and 2009 for her stories on the impact of the global financial crisis and the subsequent economic downturn on India’s economy.

By the time Mukherjee moved to Rashtrapati Bhawan, the government was under attack for “policy paralysis” – much has been written on this – its policy reforms relating to foreign investment in organised retail and insurance “were in a limbo and it had failed to make headway in implementing taxation reform.”

“Rating agencies Standard and Poor’s (S&P) and Finch downgraded their outlook on India’s sovereign rating from ‘stable’ to ‘negative’, citing slowing economic growth , high deficits and policy inaction.

“Foreign investors and the markets were spooked by Mukherjee’s provision for taxing transactions retrospectively and the planned introduction of general anti-avoidance rules targetting deals structured in such a way as to avoid payment of tax,” Mehra explains in the book’s four chapters titled The Shock (2008-09), A Recovery Destroyed ((2009-12), A Slow Recovery Again (20012-15) and Another Recovery Destroyed (2016-18).

In sum, the Mukherjee phase coincided with the “destruction” of the economy’s slight recovery post the global meltdown and the return of P. Chidambaram “with the reversal of that”.

“The difference in approach of the two ministers does seem to at least partly explain the trends during their respective tenures,” Mehra writes.

Cut to the present.

The economic slump that Narendra Modi inherited “was not as grave as the 1991 crisis, although the expectations were certainly greater”.

The country had handed him a decisive mandate for steering India towards quick and quality growth, by which more and more people could get quality jobs, health and education.

However, in four years, “the Modi government could not offer even a road map or a strategy for remaking the broken economic system. Even the GST’s game-changing potential was frittered away because of its flawed rate structure and red-tape-ridden implementation.”

“In fact, till about the half-way point in its term, the Modi government did not even spell out what in its view was the precise nature of the economic slump. Not knowing the problem, it could not come up with the right solutions. Then it realised it was the investments problem. So it took up the insolvency problem, but not bank reforms.

This was too little too late,” Mehra writes.

The author laments that in the “ten years that have been lost negotiating political setbacks, external and self-made shocks and chronic policy failures, what was called the ‘India Growth Story’ has become ‘Growth without a story'”.

“India’s start status in the global economy is fading, the growth potential is lower, the halo has crimped, the need for serious hard work is a lot more apparent than ever. The bulk of the pending backlog of reforms remains, well pending. If this lost decade demonstrated the resilience of India’s economic power, especially after the global financial crisis, its fragility was evident just the same,” Mehra contends.