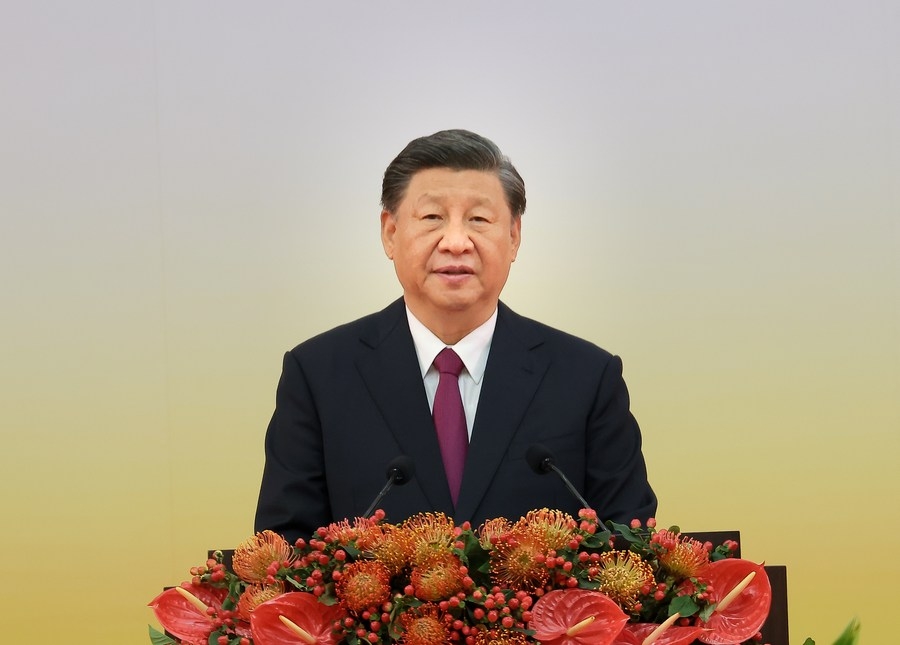

As Xi promotes his twisted form of obstreperous China-centric security designed to usurp the West, the Asia-Pacific region especially will increasingly become a battleground of ideologies….reports Asian Lite News

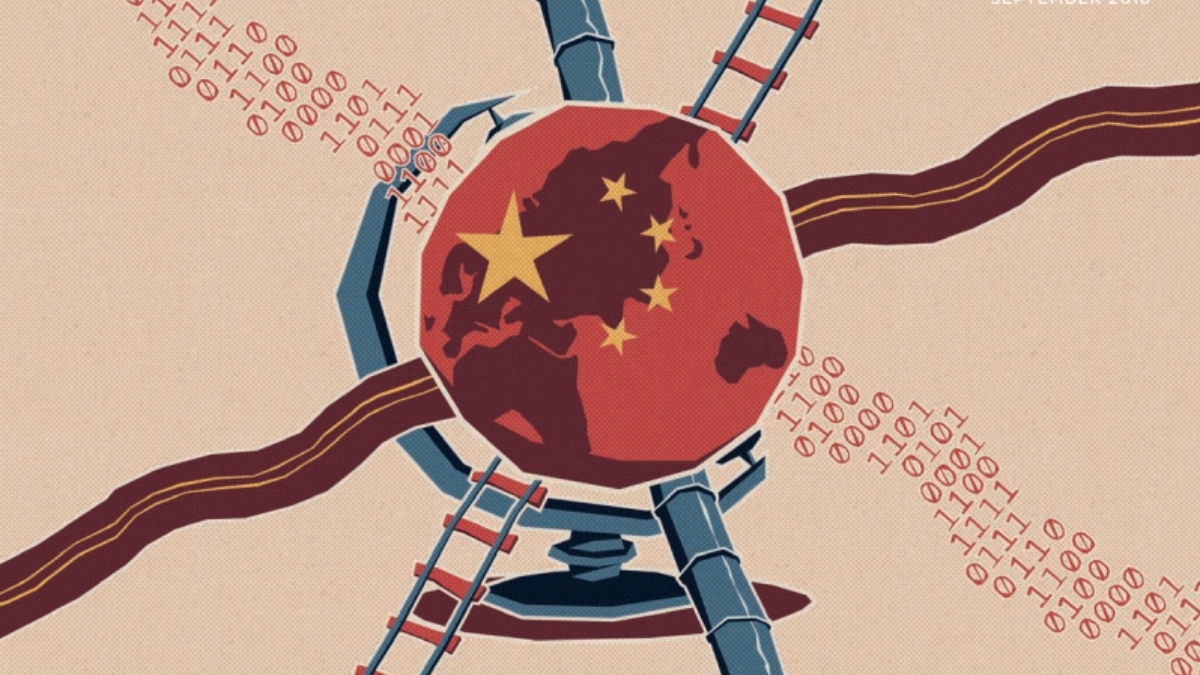

When China’s President Xi Jinping floated the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in 2013, it was unclear what it actually entailed. Perhaps Xi did not know either, for there was not even consensus on its name – it was originally labelled the Silk Road Economic Belt and 21st Century Maritime Silk Road, and then One Belt, One Road.

The BRI became a blue-ribbon project for Xi. Thus, his and, by extension, China’s prestige became dependent on its success. Now, ten years on, China has had to tighten its belt and divert the road in new directions to keep the whole concept alive. Consequently, China announced three new initiatives in 2021-22 and, although still rather vague, these are directed at gaining greater influence over the Global South, accelerating the perception of US decline, and promoting China’s warped perspective of international order.

As Xi promotes his twisted form of obstreperous China-centric security designed to usurp the West, the Asia-Pacific region especially will increasingly become a battleground of ideologies.

China is the world’s largest private lender, yet nearly 60 per cent of Chinese overseas loans today are held by countries considered financially distressed. To put this in context, in 2010 this figure was just 5 per cent.

China’s BRI plight has been magnified by COVID-19 and the Ukraine war. Indeed, Russia, Belarus and Ukraine accounted for 20 per cent of China’s overseas lending over the past two decades. China’s lending boom has truly ended, plus struggling countries like Pakistan are asking for debt restructuring.

The BRI peaked in 2018, five years ago. Although China is globally pushing its own take on security, development and digital governance, China is also, to a certain extent turning its focus inwards, returning to a centuries-old practice of retreating within its borders.

China’s narrative was that the BRI would increase connectivity and infrastructure. Indeed, China listed five priorities: coordinating policy; improving connectivity; reducing impediments to trade; integrating financial structures; and building people-to-people ties through exchanges/dialogues.

However, it rapidly morphed into a hydra where absolutely any overseas project was subsumed under its umbrella. Around 2016, Chinese investment in rail, road, port and pipeline projects boomed, but China’s economic woes have slowed down such efforts since 2018/19. There is also a noticeable trend from hard infrastructure projects towards digital infrastructure ones.

Indeed, the BRI’s future seems to rest on the Digital Silk Road (DSR), launched in 2015. As another tangent, the “Health Silk Road” projects intensified in 2020 as China exported COVID-19 vaccines and medical supplies.

Initially, BRI investment was directed towards Central Asia and Southeast Asia, before spreading westward and into Africa. Since 2018, Latin America and the South Pacific received a lot of attention. However, South Asia and Southeast Asia ultimately emerged as the main foci.

Earlier this month, the International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS) issued its annual Asia-Pacific Regional Security Assessment. Meia Nouwens, Senior Fellow for Chinese Security and Defense Policy at IISS, contributed a chapter entitled China’s Belt and Road Initiative a Decade on.

Nouwens discussed the implications for four key regions. Beginning in Southeast Asia, she said this region will remain Beijing’s chief area of strategic importance. China has been ASEAN’s largest trading partner since 2009, and the bloc has been China’s largest trading partner since 2020. Maritime routes run through Southeast Asian chokepoints too, encouraging China to push railways as an alternative.

Key recipients have been Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, the Philippines and Vietnam. Naturally, China wants Southeast Asia to be non-aligned, to serve as a bulwark against American influence.

However, China is not doing itself any favours with continual harassment of Philippine and Vietnamese commercial and law enforcement activities in the South China Sea. Western countries are leery of adopting Chinese 5G telecommunication networks, but this is not the case in many developing countries.

Nonetheless, as China exerts tighter control over domestic private-sector technology companies, this will complicate their ability to execute projects overseas. The USA’s stricter regulation of semiconductor and microchip technologies will also complicate China’s ambitions.

According to Nouwens, fear of economic dependency, ethnic tensions, project build quality and corporate social responsibility remain troubling issues for China. Ethnic tensions often result from beliefs that Chinese-led projects benefit migrant workers rather than the local population. In Indonesia, for instance, Chinese guest workers rose from 17,515 in 2015 to 30,000 in 2018.

Considering the South Asia region, unsurprisingly it is Pakistan that has received the lion’s share of BRI investment, absorbing more than half the money. China’s heavy investment in road, rail and pipeline infrastructure through the Himalayas as part of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) is not paying economic dividends, however.

Indeed, it is far more expensive to transport products overland through Pakistan than by traditional sea routes. For instance, if shifting 200,000 barrels of crude oil per day via the Burma-China pipeline, and 250,000 barrels daily through the Pakistan-China pipeline, China would lose approximately USD1 billion per year compared to the traditional seaborne tanker route.

Another estimate predicts that shipping oil from the Persian Gulf to China’s east coast would cost USD2 per barrel, whereas it would cost USD15 per barrel via the Pakistan overland pipeline. Nouwens commented, “The BRI in South Asia has achieved its intended goal of exporting Chinese industrial overcapacity abroad. From 2010-18, for example, the value of Chinese industrial goods exports to Pakistan increased from USD3.1 billion to USD8.2 billion. Nevertheless, South Asian BRI projects have faced security, political, economic, geographic and governance challenges.”

Furthermore, “Chinese investments in the region have not necessarily created more favourable conditions for Beijing’s influence. Chinese investment in South Asia has been one factor encouraging India to align more closely with the West, notably through the Quad.”

As for Central Asia, boosting ties there is helping China develop its own poorer western provinces. From 2016-21, annual China-Europe freight train journeys snowballed from 1,702 to 15,183.

Nonetheless, most trade between China and Europe still travels by sea (95+ per cent in Germany’s case), and the Ukraine war has led to a 34 per cent drop in volume via the northern rail corridor.

In the South Pacific region, Australia, New Zealand and the USA are very concerned about Chinese interests encroaching, especially since a 2018 uptick. One example is last year’s Solomon Islands-China security agreement. Nonetheless, this oceanic region attracts only a tiny proportion of BRI funds, with the largest beneficiaries being Micronesia, Papua New Guinea, Solomon Islands and Vanuatu.

Nouwens concluded, “Despite Chinese loans and grants to the sub-region, China and the BRI have made only a minimal impact in recipient Pacific Island states. There has not been any significant shift in Chinese investment or trade towards the sub-region, with the exception of Papua New Guinea. Exports from China to the South Pacific have increased twelvefold in value between 2000 and 2018, though the numbers for exports from Pacific Island countries to China have grown at a much less impressive rate.”

Samoa, Tonga and Vanuatu are the most indebted islands to China, with Tonga owing about 25 per cent of its annual GDP to the Export-Import Bank of China. Interestingly, only Solomon Islands and Kiribati signed up for new Chinese loans between 2017 and 2021.

By 2021, 64 per cent of BRI projects in Southeast Asia, the South Pacific and South Asia had been completed, according to Nouwen’s research. A further 22 per cent of projects were ongoing, and the remaining 14 per cent were still in the planning stage.

The BRI, therefore, looks rosy, right? Yet Nouwens pointed out, “…Judging implementation against these metrics risks overlooking both the fact that the last decade of BRI implementation has in some ways proved to be chaotic, and also the question of recipient countries’ agency. The BRI’s rollout in the last ten years has lacked central bureaucratic oversight and control or a coherent implementation strategy.”

The BRI was initially run under vague action plans, with existing projects simply rebadged as BRI ones. As Nouwens noted, “The reality of the BRI is that propaganda exceeds implementation, activity overtakes purpose, and actors further down the hierarchy have much latitude in interpreting the terms of their involvement. Instead of being seen as effective tools of statecraft, the BRI and DSR should perhaps be viewed as tools of the CCP’s ‘party craft’.”

For this reason, the BRI has not had the widespread impact that many Western leaders feared during its peak in 2016. “Importantly, the idea of debt-trap diplomacy turned out to be unproven, and China’s investment in nearly 60 ports worldwide has not – contrary to the expressed fears of some commentators – provided it with immediate access to a global network of dual-use ports, let alone naval bases,” the IISS researcher concluded.

Elsewhere, Lee Jones and Shahar Hameiri, in a Chatham House August 2020 research paper entitled “Debunking the Myth of Debt-Trap Diplomacy”, concluded “that the BRI is, in fact, motivated largely by economic factors. It has also shown that China’s fragmented and poorly coordinated international development financing system is not geared towards advancing coherent geopolitical aims … The BRI does not follow a top-down plan, but emerges piecemeal, through diverse bilateral interactions, with outcomes being shaped by interests, agendas and governance problems on both sides.”

China’s confused efforts, exacerbated by economic woes, have offered Western alternatives a fortuitous window of opportunity. However, to date, neither the USA nor the West has been able to offer the level of investment that the BRI has.

Additionally, Nouwens explained that “the notion that Beijing can leverage global debt as a strategic means to gain access to any and all strategic equity is a myth. Rather, it could be asked whether, instead of trapping sovereign countries in Chinese debt for strategic value, Beijing has inadvertently been caught in a debt trap of its own making.”

Fears of debt-trap diplomacy for client states have not really emerged. Ironically, China might be sufferings most from a debt trap, due to profligate and unregulated investment in the BRI’s early years, and the economic difficulties being faced by many recipients.

With the BRI facing stiffer headwinds, Xi has fine-tuned his prized BRI as he seeks to ram home perceived advantages. These three inchoate efforts are the Global Data Security Initiative (GDSI), Global Development Initiative (GDI) and Global Security Initiative (GSI).

Discussing each in turn, the GDSI was launched in 2020. Under it, China proposes a framework for data security, data storage and digital commerce. The chameleon-like concept seems to oscillate between security and the digital economy, depending on China’s target audience.

The GDI was first mentioned by Xi at a UN General Assembly meeting in September 2021. Stated priorities are “poverty alleviation, food security, COVID-19 response and vaccine, development financing, climate change and green development, industrialization, digital economy and connectivity”.

Although still unclear what the GDI actually is, more than 50 countries have joined the UN Group of Friends of the Global Development Initiative. Naturally, the GDI propagates China’s views on human rights (development is posited as a prerequisite for human rights, making human rights voluntary) and Xi’s efforts to reshape global rules and norms (where the “greater good” means that the state’s preferences override individual rights).

As for the GSI, it was first proposed in April 2022, backed up by a 21 February 2023 concept paper. That paper listed six principles: common, comprehensive, cooperative and sustainable security; respecting the sovereignty and territorial integrity of all countries; abiding by the purposes and principles of the UN Charter; taking the legitimate security concerns of all countries seriously; peacefully resolving differences and disputes between countries through dialogue and consultation; and maintaining security in both traditional and non-traditional domains.

Observers of China will have seen such phrases routinely bandied about, such as in reference to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. They will also know that these commitments are both vapid and downright disingenuous. Beijing has no intention of applying these principles to Ukraine or anywhere else, except when it is to its own advantage.

The GSI seems to replicate China’s concept of “Asia for Asians” in other regions, “which could potentially weaken the existing world order, as well as US capacity to help manage or resolve crises in other regions,” according to Nouwens. The

IISS senior fellow concluded: “These three initiatives aim to promote Chinese-centric norms and values in the Global South. This ambition will be particularly relevant in developing and emerging economies where China has invested heavily in development aid or infrastructure projects through the BRI and DSR. It also allows Beijing to continue to shape the international system in its favour at a time when large-scale infrastructure projects are not feasible due to economic conditions in China and questions of demand.”

“Beijing has previously argued that the BRI is ‘an economic cooperation initiative, not a geopolitical or military alliance’. However, these three initiatives indicate that Beijing’s engagement with the Global South is not just based on the provision of aid or helping to develop local economies; it is now expanding more formally to promote Chinese concepts of security, based closely on China’s own concept of comprehensive national security, its ‘golden prescription for global challenges’ and development, and the storage, processing and transfer of data globally according to Chinese norms.” As with BRI, it is a case of buyer beware for every initiative that China dreams up. (ANI)