The fallout of these forgotten battles was immense. China shied away from actively allying with Pakistan and the US during the 1971 India-Pakistan war. And despite several stand-offs in the past half a century, Beijing has never again launched a military offensive against India.

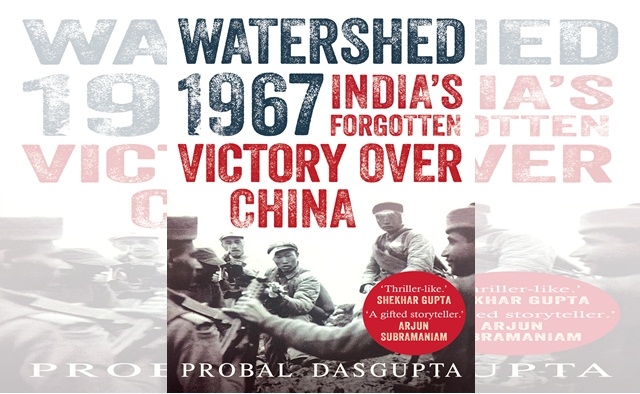

The book ‘Watershed 1967: India’s Forgotten War with China’, written by Probal Dasgupta, an ex-Indian Army officer who served in the Gorkha Regiment for several years, tells us why these battles ushered in an era of peace. It is based on extensive research and interviews with army officers and soldiers who participated in these historic battles. Here are some excerpts from the book:

The Tipping Point: A Tale of Spies and a Breach at the Watershed

For twenty-six-year-old Krishnan Raghunath, Peking was a window to discover China. As a teenager growing up in India, Raghunath had lived through the heady days of the 1950s when slogans of ‘Hindi-Chini bhai bhai’ rent the air. In his early youth in the 1960s the war ended all bonhomie between the two countries. So, as a young foreign service officer, a posting as the second secretary at the Indian embassy in Peking in 1965 was an opportunity to better understand China. At the embassy he was heading the Information Services of India (ISI). Among ISI’s challenges was to cope with the restrictions on exchange of information that the communist government posed for them in China.

June was the beginning of the summer season in Peking. Midsummer rains would pelt the city every time the temperatures rose. June 4, 1967 began as any other regular day for Raghunath. At the hour past midday, he settled into his car along with his colleague P. Vijai and set off towards the Western Hills to visit the temple of the Sleeping Buddha. Along the way, a curious Raghunath noticed the decrepit remains of another temple and stopped the car. He fished out his camera and began to take pictures of it. As he looked through the aperture of his camera to take more shots, he felt a light tap on his shoulder.

A bystander asked him why he was taking pictures in a sensitive military zone where photography was prohibited. Before Raghunath could realize what was happening, the two Indian diplomats were surrounded by soldiers of the PLA. A harried Raghunath tried to reason with the people around him that he did not mean to take photographs for any spying purposes and that he was only interested in the ruins of the temple. The Chinese, however, believed that Raghunath was using the pretext of the temple nearby to click pictures in a prohibited military zone. Upon inspection, their identity cards as embassy staffers were confiscated. The two were whisked into a vehicle and taken away. That evening, news broke about the unprecedented arrest of two Indian diplomats by Chinese authorities.

The Indian embassy immediately swung into action. The diplomats had been accused by China of spying. Denials followed and clarifications were issued that they had not indulged in any espionage activities. But China maintained that Raghunath and Vijai were taking illicit pictures in a sensitive area that had a prohibited military facility close by. The Ministry of Foreign Aff airs in Peking alleged that the diplomats had been trying to create a topographical map of a ‘prohibited area’. According to the Chinese, ‘Upon discovering them, soldiers of the Chinese PLA guarding the area immediately urged them to desist and asked them to leave. K. Raghunath and P. Vijai, however, paid no heed whatsoever and continued to hang around and take photographs of the prohibited area stealthily.’ The Chinese government withdrew Krishnan Raghunath’s diplomatic status and declared Vijai a persona non grata.

Over a week later, on June 13, about 15,000 people gathered at the Peking Municipal People’s Higher Court for the trial of the two Indian diplomats accused of spying on China. Raghunath and Vijai were ‘tried’ and found guilty of espionage. Raghunath was sentenced to ‘immediate deportation’ by the court and told to leave the country forthwith, while Vijai was given three days to leave China. However, despite the different orders, they were brought to the airport at Peking the following morning where an irate mob awaited them. Red Guards kicked and punched the Indian diplomats. A cordon of members of the Indian embassy staff who tried to protect them were also assaulted. Raghunath was forced to walk through a jeering mob of Red Guards, who jostled, kicked and spat on him. Vijai was dragged with his head shoved down, his shoes tearing off in the melee. The humiliation of the two diplomats was meant to send a loud message to India: beware.

In Delhi, the news gave rise to shock and anger and was received with angry protests from political parties. The Indian government believed that the Chinese government had violated international norms by making a film on the confessions of two Indian diplomats for use as propaganda against Indian espionage in China. The Jana Sangh, which was trying to cultivate a muscular Hindu Indian identity, seized the opportunity to try to press the government into a corner. China had thrown down the gauntlet to India’s young prime minister who had built up an early reputation for a certain kind of decisiveness that swung between foolhardiness and brilliant audacity. Indira Gandhi would respond soon.

In response to the Chinese belligerence, Chen LuChih, the first secretary of the Chinese embassy in New Delhi, was accused of gathering vital intelligence from India and carrying on subversive activities on Indian soil. Chen was stripped of his diplomatic immunity and ordered to register under the Foreigners’ Registration Act.

Unlike China, India didn’t bother with a trial. The next day, on June 14, the external affairs ministry ordered his immediate deportation to China. The government now turned towards Hsieh Cheng-Hao, who was the third secretary of the embassy, and accused him of subversive activities too. He was promptly declared persona non grata and ordered to leave India within seventy-two hours. The Indian government had responded with alacrity and unusual boldness, showing the heart to return China’s compliment. By now public emotions were riled up. The very next day after the deportation order, crowds gathered outside the Chinese embassy in Delhi, demonstrating vociferously as political parties pounced on the opportunity, instigating mobs to break into the embassy compound and go on a rampage. The mob smashed windows, set fire to a garage, tore down the Chinese flag and assaulted members of the embassy staff. That day seven members of the embassy staff, including Chen Lu-Chih and Hsieh Cheng-Hao, had to be taken to hospital.

The attack on the Chinese embassy set off alarms in Peking. Taking serious note of the violence in Delhi, the Chinese government sent a notice to Ram Sathe, the Indian charge d’affaires in Peking, that the Indian embassy staff’s safety could no longer be guaranteed. Protesters soon gathered outside Sathe’s residence, tearing down the windows of his house, sending the occupants scurrying for safety. The Indian embassy was also under siege with sixty-three men, women and children holed up inside. The hostility on both sides had crossed diplomatic lines. The danger to the lives of the diplomats on both sides was beginning to raise international concern. The likelihood of another war loomed dangerously close.

In Peking, Western diplomats rushed to intervene and decided to deliver food to the persons trapped inside the Indian embassy. But the Western food convoy was turned back by the Red Guards and the police.

India sent a note that unless the siege was lifted ‘appropriate counter measures’ would be adopted. Armed sentries arrived at the Chinese embassy in New Delhi the following day with specific instructions for the Chinese diplomats: the occupants were ordered not to leave the building. India was not about to back off, even if it meant that the embassy staff in both countries ended up being detained as prisoners.

Looking for a possible detente, the Chinese foreign ministry suggested sending an aircraft to Delhi to bring back their diplomats injured in the attack in Delhi. The Indian government responded with a similar request for its diplomats holed up in Peking. China, however, turned down their request. But they didn’t seem to anticipate that India was in no mood to capitulate. The following day, as a Chinese aircraft touched down in Delhi to take back the diplomats, the government in Delhi refused to provide refuelling facilities for the aircraft. Finally, after assurances, an injured Hsieh Cheng-Hao was allowed to leave Delhi on June 21. Chen Lu-Chih was kept under detention and deported three days later.

The demonstrations outside the Indian embassy in Peking, somewhat staged, were called off soon after. Sathe was told that the embassy staff were free to leave the compound and return to their flats. The Indians responded with a reciprocal gesture and withdrew their sentries at the Chinese embassy. The staff could now step out of the embassy in Delhi, though their personal safety remained unguaranteed.

India had matched China for every stride and even outwitted the adversary on occasions. After having mirrored each other’s unyielding and harsh steps, peace overtures from both sides also started to mimic each other. An uneasy truce was established and the ugly diplomatic fracas didn’t blow up into a military crisis. Th e bickering, though, resumed when the Chinese embassy accused Indian customs of seizing literature that contained Mao Zedong’s works. The Indian government, their note complained, was preventing the Chinese staff from their right to study Mao’s thought. To the Chinese, this was the larger conspiracy of capitalism at play.

The rivalry between India and China had begun to worry the West. The diplomatic stand-off had attracted international attention and shortly manifested itself on the border. As if on cue, attention turned to the tiny Himalayan outpost of Nathu La.

Since 1965 the Chinese had been attempting to dominate the border by various means. They used to make regular broadcasts from loudspeakers at Nathu La, pointing out to Indian troops the pathetic conditions in which they lived, their low salaries and lack of amenities, comparing them to those enjoyed by Chinese officers. Sagat had loudspeakers installed on the Indian side and played similar messages in Chinese every day. Throughout 1966 and early 1967, Chinese propaganda, intimidation and attempted incursions into the Indian territory continued. As mentioned earlier, the border was not marked and there were several vantage points on the watershed which both sides thought belonged to them. Patrols which walked along the border often clashed, resulting in tension, and sometimes even casualties.