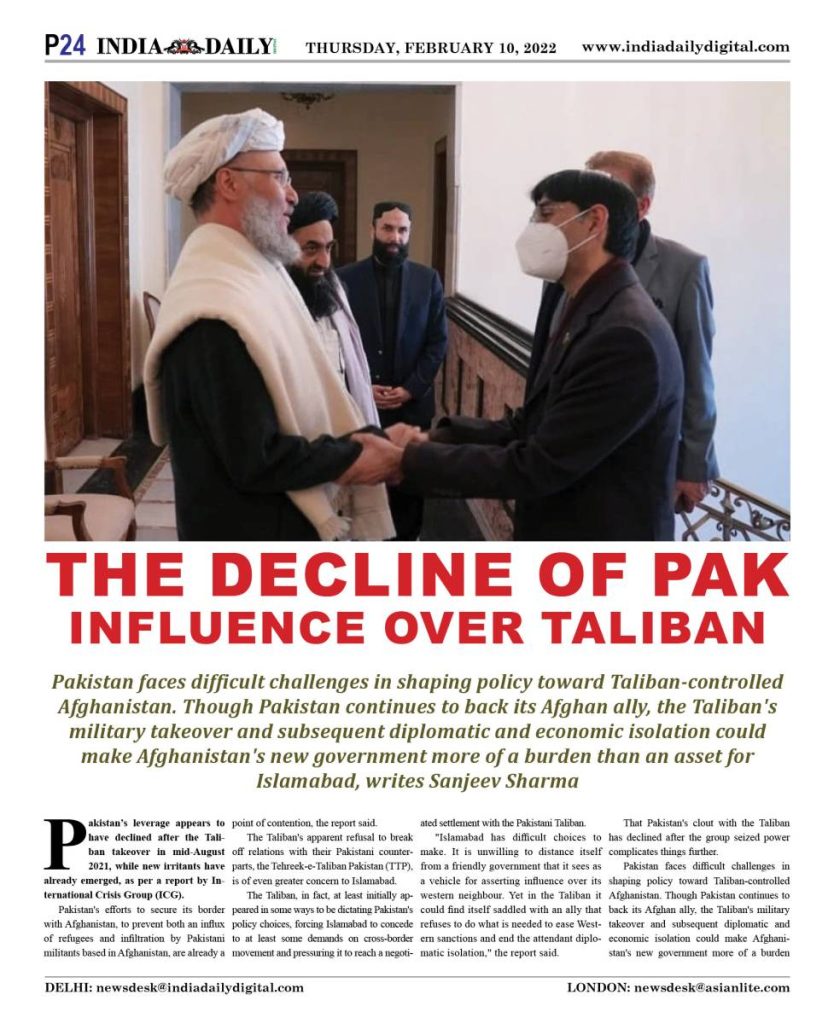

Pakistan faces difficult challenges in shaping policy toward Taliban-controlled Afghanistan. Though Pakistan continues to back its Afghan ally, the Taliban’s military takeover and subsequent diplomatic and economic isolation could make Afghanistan’s new government more of a burden than an asset for Islamabad, writes Sanjeev Sharma

Pakistan’s leverage appears to have declined after the Taliban takeover in mid-August 2021, while new irritants have already emerged, as per a report by International Crisis Group (ICG).

Pakistan’s efforts to secure its border with Afghanistan, to prevent both an influx of refugees and infiltration by Pakistani militants based in Afghanistan, are already a point of contention, the report said.

The Taliban’s apparent refusal to break off relations with their Pakistani counterparts, the Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP), is of even greater concern to Islamabad.

The Taliban, in fact, at least initially appeared in some ways to be dictating Pakistan’s policy choices, forcing Islamabad to concede to at least some demands on cross-border movement and pressuring it to reach a negotiated settlement with the Pakistani Taliban.

“Islamabad has difficult choices to make. It is unwilling to distance itself from a friendly government that it sees as a vehicle for asserting influence over its western neighbour. Yet in the Taliban it could find itself saddled with an ally that refuses to do what is needed to ease Western sanctions and end the attendant diplomatic isolation,” the report said.

That Pakistan’s clout with the Taliban has declined after the group seized power complicates things further.

Pakistan faces difficult challenges in shaping policy toward Taliban-controlled Afghanistan. Though Pakistan continues to back its Afghan ally, the Taliban’s military takeover and subsequent diplomatic and economic isolation could make Afghanistan’s new government more of a burden than an asset for Islamabad, it added.

Growing instability and economic hardship could lead impoverished Afghans to seek shelter in Pakistan. Islamabad’s alliance with the Taliban could also strain relations with the U.S. and other Western countries. Most importantly, the Taliban’s failure to take action against Pakistani militants operating from Afghan territory could endanger Pakistan’s internal security, the report said.

Islamabad’s hesitancy to take the plunge this time around is primarily driven by concern that no other government worldwide, including among Afghanistan’s other neighbours, has yet taken the step of recognition.

Unilateral action by Pakistan would likely strain relations with powerful Western countries, particularly the US, Islamabad also realises that recognition in itself would do little to ease the Taliban’s diplomatic and economic isolation.

Islamabad is well aware, however, that the Taliban must also assuage international concerns with regard to both governance and security if Western pressure is to let up.

While Pakistan is encouraging the Taliban to opt at the very least for a façade of inclusive government and demonstrate at least token respect for basic rights, the Taliban have yet to heed its advice. Nor has Islamabad succeeded in convincing the militant group-turned-government to break links with Afghanistan-based jihadi outfits such as Al Qaeda, the report said.

Concerned about such inaction on the Taliban’s part, even countries such as Iran, China and Russia that have opted for closer engagement with the Taliban government are unlikely to officially recognise it any time soon. The odds are even lower that the US and its Western allies will recognise the Taliban government and lift all sanctions so long as the Taliban show no willingness to compromise.

Given its closeness to the Taliban, Islamabad could itself face Western pressure, aimed at compelling it to work harder at convincing its Afghan allies to respond more positively to international demands. Cooler relations with the U.S. could become particularly onerous given Washington’s weight in international financial institutions, such as the World Bank and International Monetary Fund, on which Pakistan is dependent to prop up its floundering economy, the ICG said.

Islamabad is also concerned about the cross-border implications of Afghanistan’s economic and diplomatic crises. Afghanistan’s economic collapse is depriving Pakistan of opportunities to revive trade ties that had been badly eroded by frictions with erstwhile Afghan President Ashraf Ghani’s government.

Growing insecurity and economic hardship could translate into thousands, possibly hundreds of thousands, of impoverished Afghans seeking shelter and livelihoods in Pakistan, the report said.

Terrorists may shift allegiance to ISIL-K

The Taliban views ISIL-K as its primary kinetic threat, as the group aims to position itself as the chief rejectionist force in Afghanistan, with a wider regional agenda threatening neighbouring Central and South Asian countries, as per a UN report.

Member States estimated that, if Afghanistan descends into chaos, some Afghan and foreign extremists may shift allegiances to ISIL-K, which continues to be led by Sanaullah Ghafari (alias Shahab alMuhajir), an Afghan national.

Aslam Farooqi, a former ISIL-K leader, escaped from prison and has subsequently rejoined the group in a senior role. The former leader of ISIL-K, Abu Omar al-Khorasani, was killed by the Taliban in August, shortly after it took control of the prison in which he was being held.

Member States assess that the strength of Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant – Khorasan (ISIL-K) has now risen from earlier estimates of 2,200 to approaching 4,000, following the release of several thousand prisoners. One Member State assessed that up to half of ISIL-K is composed of foreign terrorist fighters. Although the group controls limited territory in eastern Afghanistan, it is capable of conducting high-profile and complex attacks, such as the 27 August bombing at Kabul airport, in which more than 180 people were killed, and several subsequent attacks.

Central Asian terrorist groups Islamic Jihad Group (IJG), Khatiba Imam al-Bukhari (KIB) and Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU) which actively participated in fighting alongside the Taliban, are now experiencing greater freedom of movement in the country.

Central Asian embassies based in Afghanistan have observed with concern that several leaders of those groups have travelled freely to Kabul. IJG, led by Ilimbek Mamatov, a Kyrgyz national, and his deputy, Amsattor Atabaev of Tajikistan, is assessed to be the most combat-ready Central Asian group in Afghanistan.

It operates primarily in Badakhshan, Baghlan and Kunduz Provinces. KIB, led by Dilshod Dekhanov, a Tajik national, is currently located in the Bala Murghab district of Badghis Province. The group’s strength has increased through the recruitment of local Afghans.

In September, Mamatov and Dekhanov separately visited Kabul. Each leader lobbied for support from the Taliban to unify the Central Asian groups under their respective leadership, in recognition of their contributions to the Taliban victory. The Taliban reportedly rejected the proposals, preferring to incorporate the groups as distinct military units within the newly established Taliban army, the UN report said.