These debts are systematically underreported to the World Bank’s Debtor Reporting System…reports Sanjeev Sharma

Forty-two countries now have levels of public debt exposure to China in excess of 10 per cent of GDP.

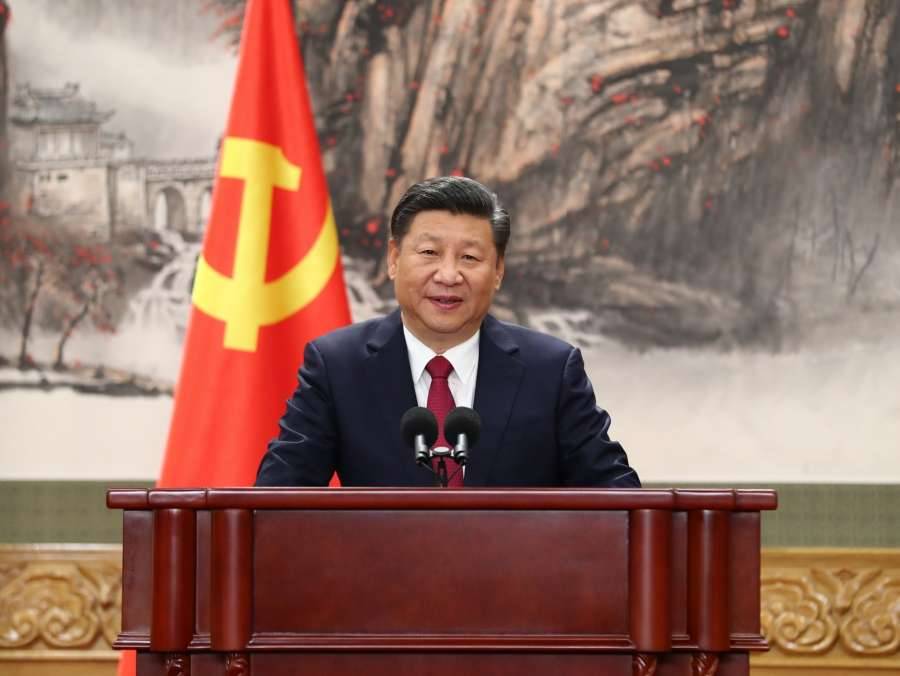

AidData, an international development research lab based at William & Mary’s Global Research Institute, today released a trove of new findings about China’s secretive overseas development finance program leveraging insights from a uniquely granular data that captures 13,427 projects across 165 countries worth $843 billion. These projects were financed by more than 300 Chinese government institutions and state-owned entities. This includes a special emphasis on Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

These debts are systematically underreported to the World Bank’s Debtor Reporting System (DRS) because, in many cases, central government institutions in low-income and middle-income countries are simply not the primary borrowers responsible for repayment, says a research by AidData.

According to Brad Parks, AidData’s Executive Director and a co-author of the report, “these unreported debts are worth approximately $385 billion and the hidden debt problem is getting worse over time”.

He and his co-authors find that average annual underreporting of repayment liabilities to China was $13 billion during the pre-BRI era, but $40 billion during the BRI era. The average government, they estimate, is underreporting its actual and potential repayment obligations to China by an amount that is equivalent to 5.8 per cent of its GDP.

Parks explained that “the challenge of managing these hidden debts is less about governments knowing that they will need to service undisclosed debts to China with known monetary values than it is about governments not knowing the monetary value of debts to China that they may or may not have to service in the future.”

35 per cent of the BRI infrastructure project portfolio has encountered major implementation problems—such as corruption scandals, labor violations, environmental hazards, and public protests—but only 21 per cent of the Chinese government’s infrastructure project portfolio outside of the BRI has encountered similar problems. BRI infrastructure projects are also taking substantially longer to implement than Chinese government-financed infrastructure projects undertaken outside of the BRI, and Beijing has witnessed more project suspensions and cancellations during the BRI era than it did during the pre-BRI era.

“Host country policymakers are mothballing high-profile BRI projects because of corruption and overpricing concerns, as well as major changes in public sentiment that make it difficult to maintain close relations with China. It remains to be seen if ‘buyer’s remorse’ among BRI participant countries will undermine the long-run sustainability of China’s global infrastructure initiative, but clearly Beijing needs to address the concerns of host countries in order to sustain support for the BRI,” said Brooke Russel, an Associate Director at AidData and one of the other co-authors of the report.

“China has quickly established itself as the financier of first resort for many low-income and middle-income countries, but its international lending and grant-giving activities remain shrouded in secrecy,” said Ammar A Malik, a Senior Research Scientist at AidData. Beijing’s reluctance to disclose detailed information about its overseas development finance portfolio has made it difficult for low-income and middle-income countries to objectively weigh the costs and benefits of participating in the BRI.

Malik and his colleagues found that, during the pre-BRI era, China and the U.S. were overseas spending rivals. However, China is now outspending the U.S. and other major powers on a more than 2-to-1 basis. In an average year during the BRI era, China spent $85 billion on their overseas development program as compared to the U.S.’s $37 billion. Banking on the Belt and Road demonstrates that Beijing has used debt rather than aid to establish a dominant position in the international development finance market. Since the BRI was introduced in 2013, China has maintained a 31-to-1 ratio of loans to grants.

The country’s “policy banks”—China Eximbank and China Development Bank—led a major expansion in overseas lending in the run-up to the BRI. However, since 2013, state-owned commercial banks—including Bank of China, the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China, and China Construction Bank—have played an increasingly important role, with their overseas lending activities increasing five-fold during the first five years of BRI implementation. The number of “mega-projects”—financed with loans worth $500 million or more—approved each year also tripled during the BRI era.

The report finds that as China has financed bigger projects and taken on higher levels of credit risk, it has also put in place stronger repayment safeguards. 31 per cent of the country’s overseas lending portfolio benefited from credit insurance, a pledge of collateral, or a third-party repayment guarantee during the early 2000s, but this figure now stands at nearly 60 per cent.